I am currently enjoying an extended paternity leave, but this does not mean that I can completely step away from my practice; nor would I want to. In between winding the baby, reading various Julia Donaldson books to the toddler, and repeatedly cleaning our home to a standard that a Colour Sergeant at Sandhurst would not shout at me, I have been considering Awaab’s law, formally known as The Hazards in Social Housing (Prescribed Requirements) (England) Regulations 2025 (‘the 2025 Regulations’) in depth.

This blogpost will set out what I consider to be three interesting observations in respect of the Regulations. The usual disclaimer applies in respect of this blogpost being my opinion only, and it does not equate to legal advice. Indeed, some of these observations may ultimately be ‘non-points’, or instead be addressed very quickly by the first appeal judgments that we see concerning these cases. There is also the very realistic possibility that I have a sleep-deprived, nutrient-deficient baby-brain and that I am either overthinking some points, or god forbid, I am just wrong – but this is my blog and that brings with it the privilege of sharing my thoughts.

A recap

Let’s start with a very brief recap for those that have either been living under a rock, or in the more likely scenario, are new to housing disrepair. Housing disrepair claims are by and large a creature of contract law. Repair obligations imposed on the landlord (in normal speech: what the landlord must repair) may be set out expressly in writing within the contract, or instead are implied into the contract by a matter of law.

S.11 of the Landlord and Tenant Act 1985 (’s.11 LTA 1985’) implies a term into the contract that the landlord must, in a nutshell, keep in repair the structure and exterior of the property; the installations in the property for the supply of water, gas and electricity and for sanitation; and the installations in the property for space heating and heating water. On the back of this, lots of arguments were had over the years as to what fell within the remit of s.11 LTA 1985. For example, does the landlord have to repair the plaster? What about extractor fans? How about kitchen units? And so on.

Now a real issue that started to arise was damp and mould. This is because, under s.11 LTA 1985, damp and mould is not disrepair in and of itself: it is a symptom of disrepair. For example, damp and mould may have arisen as a result of condensation in a property, because the tenant was constantly drying their clothing on the radiators. I have more to say in respect of this argument later.

Conversely, damp and mould may have arisen due to water ingress. For example, rainwater could be getting in somehow due to deficient brickwork which causes damp and mould internally.

Fast forward some 33 or so years later and we have the Homes (Fitness for Human Habitation) Act 2018 which introduced a new obligation: s.9A LTA 1985. This implied term really shifted matters in favour of securing safer homes, in that a landlord has to ensure that a property is fit for human habitation with reference to specific conditions set out in s.10 LTA 1985 and Schedule 1 of the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (England) Regulations 2005. Like any new law that involves litigation (and therefore the spending or receiving of money), lots of arguments have been had in relation to this. What does ‘fit for human habitation’ mean? Does an expert have to have experience/qualifications in the application of the 2005 regulations? Etc.

Just for completeness at this juncture, this was not the first time a fitness for human habitation clause was introduced by the law. A similar obligation was introduced by s.6 of the Housing Act 1957, as amended by the Local Government Act 1963. However, this obligation only applied to properties in which a ridiculously low rent was charged, so this had practically very little effect.

Now a common thread across both s.11 and s.9A LTA 1985 is that the landlord would only be liable if they were placed on notice of the disrepair/hazard, and that a ‘reasonable period of time’ had passed in which they had still failed to complete the repairs/make the property fit for human habitation. What flows from this, as you probably guessed, are lots of arguments as to what a ‘reasonable period of time’ is. Over the years, there have been many factors proffered to the Court for unduly lengthy periods of time: covid, planned repairs, lack of resources, etc.

Despite the implied obligations as set out above, a disgraceful event occurred when a two-year-old child (Awaab Ishak) died in December 2020 as a result of a severe respiratory condition. The coroner eventually found that his death was caused by prolonged exposure to black mould in the property which itself had inadequate ventilation which led to excess damp and condensation. This horrific stain on the conscience of this country was entirely avoidable.

What rightly followed (in my view), was another fairly significant shift in the law in the form of Awaab’s law. Awaab’s law (again, the 2025 Regulations) contain detailed obligations on the landlord which are implied into contract, largely in respect of timeframes as to when inspections and repairs must be completed. This is, in my view, also beneficial to landlords in that it aimed to bring about a degree of certainty, which would of course help with the analysis of whether the landlord was facing a plausible breach of contract case, or not. My view is that these Regulations arise from the best intentions, but the wording of them is such that it is going to give rise to a significant amount of litigation.

What are the obligations?

This blogpost is not long enough to go into a deep dive into the 2025 Regulations, but this is quite helpful.

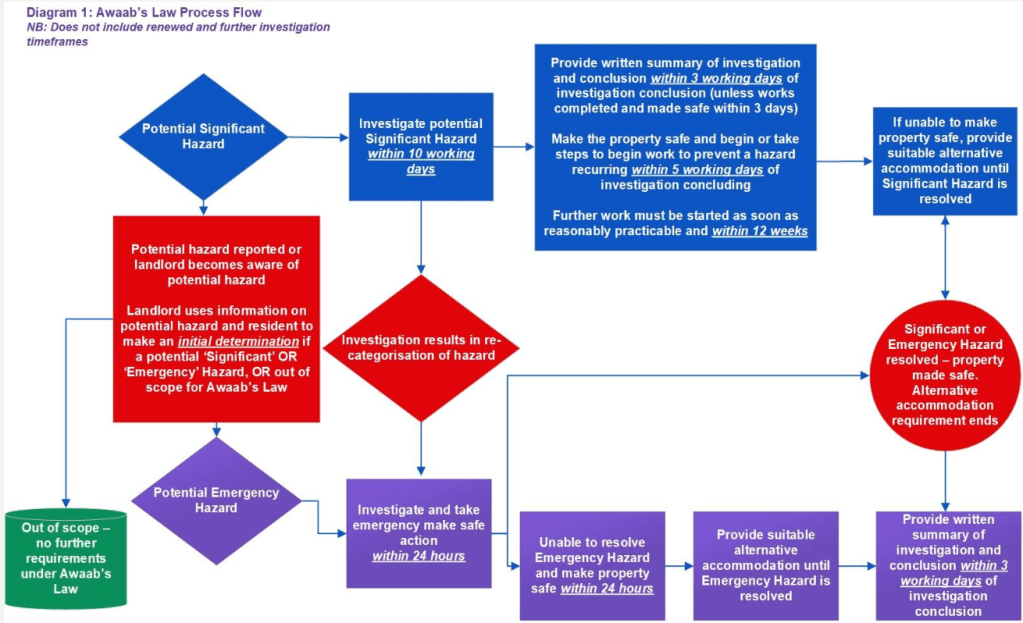

The image below also sets out some of the obligations in the most basic form, which is all that is really needed for me to make some of the points in this blogpost:

It is clear that, factually, a number of scenarios can unfold. Some are more straightforward than others. For example:

- The landlord completely fails to complete an investigation despite being on clear notice;

- The landlord completes an investigation, agrees that there are hazards, but this investigation was completed out of time; or

- The landlord completes an investigation, either on time or not, but disagrees that there are hazards present, or alternatively, that the hazards are minor and do not reach the threshold of either being a ‘serious’ or ‘emergency’ hazard.

It is important to note that the landlord must be placed on notice of the ‘relevant matter’ after the 27th October 2025 (Reg 21).

In the first scenario, as the landlord is required to complete a ‘relevant investigation’ within set timeframes after being placed on notice, if the landlord fails to complete an investigation within these timeframes then they will be in breach of contract. However, this does not necessarily mean that the tenant will have a successful case in law. Context will be key following this breach.

For example, if the inspection takes place just a day late, then the Defendant is likely to successfully argue that there is no loss flowing from the breach of contract. I suspect the no loss argument, or alternatively that any loss is de minimis, will be used in almost every defence to these cases. I surmise that the merit of the arguments will then depend ultimately on whether there are found to be significant or emergency hazards within the home. In those cases where the landlord was both late to complete an inspection, and there were hazards found, the Claimant is likely to succeed.

What is more interesting though are the cases where the tenant has reported a ‘relevant matter’; the landlord investigates the matter months late (in breach of contract as it is outside the time periods set out above); and the landlord finds that the hazards do not in fact reach the thresholds. The tenant will argue that there has nonetheless been a breach of contract. The landlord will say that there is no loss. The tenant will counter-argument by saying that the 2025 Regulations impose ‘must’ obligations and that their loss was the worry and stress caused in waiting for the landlord to complete an inspection as they are otherwise contractually required to do.

Another interesting point is that the landlord has another line of defence for potential emergency hazards, which does not exist for potential significant hazards. For significant hazards, under Reg 6, the landlord must complete an inspection when they become aware of an issue of concern in the property and also when condition 1 in Reg 5 (reason to believe emergency hazard affecting home) does not apply. Simple enough.

However, condition 1 of Reg 5 has an extra provision. Condition 1(a) is drafted in the same terms: ‘becomes aware of an issue of concern in relation to the social home’. So far so good. However, Condition 1(b) reads: ‘[the landlord] has reasonable grounds to believe that there is an emergency hazard affecting the social home…’ ‘Has reasonable grounds to believe’ will likely bring with it defences that either the landlord did not have reasonable grounds to believe that there was an emergency hazard affecting the social home, or alternatively encourage defendants to take an overly strict approach in the defence in putting the claimant to proof in respect of notice. I can see defendants requiring claimants to prove points along the following lines: when the defendant was put on notice, specifically to what extent was the level of damp and mould communicated, who was this communicated to, etc. Whether this overly strict approach ultimately works is a different question, but I find it curious that the words ‘has reasonable grounds to believe’ were inserted into the 2025 Regulations. Having seen the technical arguments raised in these cases for many years, I believe that this additional wording has the potential to lead to some messy technical arguments which all detract from the point: that the tenant is potentially suffering quite seriously from the effects of hazards in the property.

Following the above, the answer to the second scenario has been addressed. It all depends on context and any delay would likely feed into the level of damages awarded in that scenario.

The third scenario is when things get really tricky, and I will touch on some of the points below.

Against that backdrop, I want to explore the three points in the 2025 Regulations that I further find to be interesting.

Observation 1 – The definition of ‘competent investigator’

Reg 2 sets out the interpretation of the Regulations. “Competent investigator” means a person that, in the reasonable opinion of the lessor, has the skills and experience necessary to determine whether a social home is affected by a significant hazard or emergency hazard. ‘In the reasonable opinion of the lessor’ has been bothering me for some time now. Why does this matter?

Well, Reg 6 sets out the requirement for the investigation of (non-emergency) hazards. Reg 6(2) provides: ‘The lessor must secure that an investigation of the relevant matter is completed by a competent investigator before the end of…’

So now we have two requirements. Firstly, the landlord ‘must secure’. The second is that the investigator has the skills and experience necessary ‘in the reasonable opinion of the lessor’. This is conceptually very difficult.

Let’s explore this with a very likely scenario. A tenant complains of serious damp and mould in the property in November 2025. A high-quality, detailed letter of claim is sent in December 2025 (for the purposes of this let’s ignore any arguments that the defendant may raise about a lack of detail etc). The requirements of Reg 6 are clearly met yet the landlord fails to complete an investigation. The tenant follows the Pre-Action Protocol and gets their own expert report from a qualified surveyor with 25 years of experience. That surveyor finds that there is severe damp and mould caused by a combination of water ingress and a lack of ventilation due to broken extractor fans.

Putting aside the s.9A LTA 1985 claim because that is distinct from a 2025 Regulations claim, the tenant may wish to argue that the investigation completed by their highly experienced qualified surveyor meets the standard of ‘competent investigator’. You can certainly see why they would make this argument. They then say that a further investigation by the landlord is not needed, and instead the landlord just needs to complete the works: be that to make the home safe or to prevent the hazards from arising again. This all makes sense so far and certainly seems sensible. The tenant has effectively done the landlord’s job for them in arranging an inspection by a competent investigator.

However, I may be being cynical, but would it not be open to the landlord to argue that they (i.e. the landlord) did not ‘secure’ an investigation (as the tenant instructed an expert, not the landlord), and further that in their ‘reasonable opinion’ that person lacked the skills and experience (the landlord will probably say that the person is not able to assess individual vulnerabilities of the occupiers etc)? That said, I suppose if the landlord made those arguments, they would be admitting that the investigation was not completed within the timeframes, which itself is a breach of contract. But in any event, would the Court then be assessing whether the Claimant’s expert had the necessary skills and experience (which is a distinct test as compared to who can be an expert under Part 35), or would it instead be assessing whether the landlord’s opinion as to the alleged lack of skills and experience was reasonable (or not). If, in the end, the landlord’s opinion as to reasonableness was accepted by the court, would this mean simply that an inspection by a competent investigator was not completed and the 2025 Regulation claim fails (save for the fact that, again, in this scenario the landlord must be taken to admit that they did not complete an investigation in time)?

Further, would the tenant be seeking specific performance for the landlord to complete an investigation as required by the 2025 Regulations? This itself causes difficulties. Imagine waiting 18-24 months for a trial, only for the court to award specific performance in that the landlord must go out and investigate the hazards that have already been addressed in length in evidence. What if the landlord then completed the investigation and found that the threshold for ‘significant’ or ‘emergency’ hazard had not been met. Where would this leave the tenant? Of course, thinking pragmatically, as the 2025 Regulations are but one cause of action, the reality is that the Court would just order the Defendant to complete the required works (due to the successful s.11/s.9A/express obligations cause of actions), but it nonetheless raises some interesting conceptual points.

What about the alternative scenario in which the landlord does complete an investigation in time but uses say a non-qualified technical officer, and this technical officer concludes that the issues do not reach the threshold of ‘significant’ or ‘emergency’. The landlord decides to argue that nonetheless in their ‘reasonable opinion’ this person had the skills and experience necessary. Let’s say the tenant’s expert, and the tenant, have a very different view in respect of the hazards. Would the tenant’s pleaded case not be that there were significant or emergency hazards present in the property and that the landlord’s investigator was wrong, but instead/in addition that the landlord could not have reasonably opined that this person had the necessary skills and experience. This is a different argument, and again if it is not pleaded correctly, I expect to see technical arguments surrounding this. But again, whether those technical arguments ultimately succeed is a separate point.

Observation 2 – The difference between s.9A LTA 1985, ‘significant’ and ‘emergency’ hazards

The difference between ‘significant’ and ‘emergency’ hazards is set out at Reg 3(1):

(a) “significant hazard” means, in relation to a social home, a relevant hazard that poses a significant risk of harm to the health or safety of an occupier of the social home;

(b) “significant risk of harm” means a risk of harm to the occupier’s health or safety that a reasonable lessor with the relevant knowledge would take steps to make safe as a matter of urgency (but not within 24 hours);

(c) “emergency hazard” means, in relation to a social home, a relevant hazard that poses an imminent and significant risk of harm to the health or safety of an occupier of the social home;

(d) “imminent and significant risk of harm” means a risk of harm to the occupier’s health or safety that a reasonable lessor with the relevant knowledge would take steps to make safe within 24 hours.

These definitions themselves are going to give rise to lots of evidential arguments concerning the difference between ‘significant risk of harm’ and ‘imminent and significant risk of harm’. Expert evidence will be helpful here, as well as a detailed account of a tenant’s particular vulnerabilities and how the hazards in the property specifically impact them.

What is also fairly interesting to note at this stage is that in addressing s.9A LTA 1985 claims, a landlord will often point to the opinion of the claimant’s expert who may opine that a decant is not required. Now, of course, under the 2025 Regulations, if relevant safety work is not completed in time, then the landlord must decant the tenant. This is interesting because if the landlord finds that a ‘significant’ or ‘emergency’ hazard existed in the property, and that the property was not made safe within time, then by extension the court must find that the tenant was entitled to be decanted from the property and by extension is likely to find that the property was not fit for human habitation under s.9A LTA 1985 (because it has found that the tenant ought to have been decanted from the property as it was not safe to remain there).

Let’s turn now to the definition of s.9A LTA 1985 and the case of Jillians v Red Kite Community Housing (Oxford County Court, 24th September 2024). Now whilst only a non-binding County Court decision, it was nonetheless provided by an experienced Circuit Judge and argued by experienced housing disrepair counsel. Paragraph 30 is of use here:

I accept Mr Murray’s submission that the Defective Premises Act authorities are of relevance to claims made pursuant to section 9A LTA. The requirements under section 1 Defective Premises Act (“fit for habitation”) and section 9A LTA (“fit for human habitation”) are not identical but given the Court of Appeal’s definition set out above, which is tied to the health, safety, inconvenience or discomfort to the occupants, it appears to be a distinction without a material difference. Similarly, the guidance of the Court of Appeal in Rendlesham relating to section 1 Defective Premises Act, that dwellings which are not fit for habitation are those ‘capable of occupation without risk to the health and safety of, and without undue inconvenience or discomfort to the occupants’ (I paraphrase) seems also to fall within the test in section 10 LTA as neither case could it be said that such dwellings are “reasonably suitable for occupation in that condition”, and section 10 LTA includes within it long-established concept of “hazards” under the Housing Act 2004, being any “risk of harm to the health or safety of an actual… occupier of a dwelling”, and ‘prescribed hazards’ under section 2 of that Act. Of course, as Mr Murray submits, the Defective Premises Act was concerned with fitness for habitation at the time of completion of the building of a dwelling, and for a reasonable time afterwards, and section 9A LTA is a continuing obligation during the period of a lease, but I am satisfied that the principles set out in Bole v Huntsbuild and Rendlesham are applicable to section 9A LTA, save that they must be applied taking into account that difference.

It can be seen therefore that there are differences between the three definitions. It appears to me that ‘significant risk of harm’ is obviously of a less serious nature. It will be interesting to see whether the Court eventually finds the definition of unfitness to be met in cases that only involve significant hazards, or instead whether it places emergency hazards and unfitness on the same footing. Or instead whether the three definitions will eventually become a hierarchy, or spectrum, of severity.

Observation 3 – Vulnerability

I mention this one only because I am considering a lengthy research piece on vulnerability in respect of social housing tenants, and I find this interesting. When we consider contract law and the actions of the individuals at hand, we are thinking of the ‘reasonable man’. This is an objective, hypothetical standard that we all learned about in law school. However, it is useful to pause and think about who this ‘reasonable man’ is. I don’t intend to become too analytical here, but he is probably working/middle class, he holds down a job, probably has a family, he has normal levels of intelligence, and moderate levels of resilience.

However, a lot of social housing tenants cannot relate to the ‘reasonable man’. They may have crippling mental health issues or severe economic issues that render them vulnerable.

Now, what I do like about the 2025 Regulations (albeit vulnerability is not expressly mentioned therein), is that consideration does now have to be made for the particular needs and vulnerabilities of the tenant/occupier.

In the gov guidance for social landlords it says:

’To enable landlords to categorise and triage hazards they should take reasonable steps to understand the circumstances of the tenant, including any vulnerabilities of the household which could worsen the potential impact of the hazard such as age, health conditions or disability.’

…

‘It is therefore important that social landlords maintain accurate and up-to-date information about their properties and the individuals living in them. This includes recording any details shared by tenants that may indicate increased vulnerability to specific hazards, such as physical or mental health conditions, and noting preferred methods of contact and any reasonable adjustments, for example relating to language, communication preferences, or support needs.’

I do recognise that the HHSRS Operating Guidance makes reference to vulnerabilities, particularly in relation to age, but the 2025 Regulations go far beyond this.

In my view, this is very positive. However, putting my cynical housing disrepair litigator hat on, I can see it giving rise to lots of evidential issues. ‘Where is the expert evidence that damp and mould exacerbates asthma’ shouts the landlord. Or conversely, we may see tenants saying that they have communicated vulnerabilities to the landlord, but there is not a shred of contemporaneous evidence to verify the tenant’s statements.

Just one more point on vulnerabilities. Social housing tenants are often economically vulnerable. This point relates to the argument that damp and mould has been caused by condensation which itself has been caused by lifestyle choices. The ‘lifestyle choices’ that usually arise in court are drying clothes within the property (a social housing tenant may not be able to afford a car to drive their laundry to a local drying service) and boiling water (for example, cooking rice or potatoes). Thankfully, the guidance dispenses with a lot of these arguments:

‘It is unacceptable for social landlords to assume that the cause of a hazard, such as damp and mould, is due to the tenant’s ‘lifestyle’. Social landlords should not make assumptions and fail to take action or to investigate a damp and mould hazard on the basis of, for example, condensation they attribute to the tenant’s ‘lifestyle’. It is unavoidable that everyday tasks, such as cooking, bathing, washing and drying laundry will contribute to the production of indoor moisture. These activities are unlikely to constitute a breach of contract on the part of the tenant and, therefore, should not be a reason not to take action through Awaab’s Law.’

In fairness, these arguments have always been weak and often resulted in a judicial eyebrow raise. Stronger arguments may be that the tenant turned off the extractor fan and sealed up the trickle vents. Those are the sorts of points that ought to be raised in defences.

Conclusion

As I made clear at the start of this blogpost, these are just my observations and thoughts. Observations and thoughts prepared whilst sleep-deprived and away from work for an extended period of time. I nonetheless find these issues interesting and I am looking forward to seeing these arguments unfold over the next few years.

Lots of other interesting points stem from the 2025 Regulations. How do they align with the pre-action protocol? Ought they be used more routinely for the obtaining of injunctions? What about cases in which the landlord has failed to meet the other obligations such as the requirement to keep the property safe, or to keep the tenant updated, or to provide the required safety advice? Will the landlord simply argue again that no loss flows from the breach? These are all points that will hopefully become clearer in time.